Introduction - Harkers Island

A bright spot of earth, the place of my birth … Twisted oaks and my kinfolks.

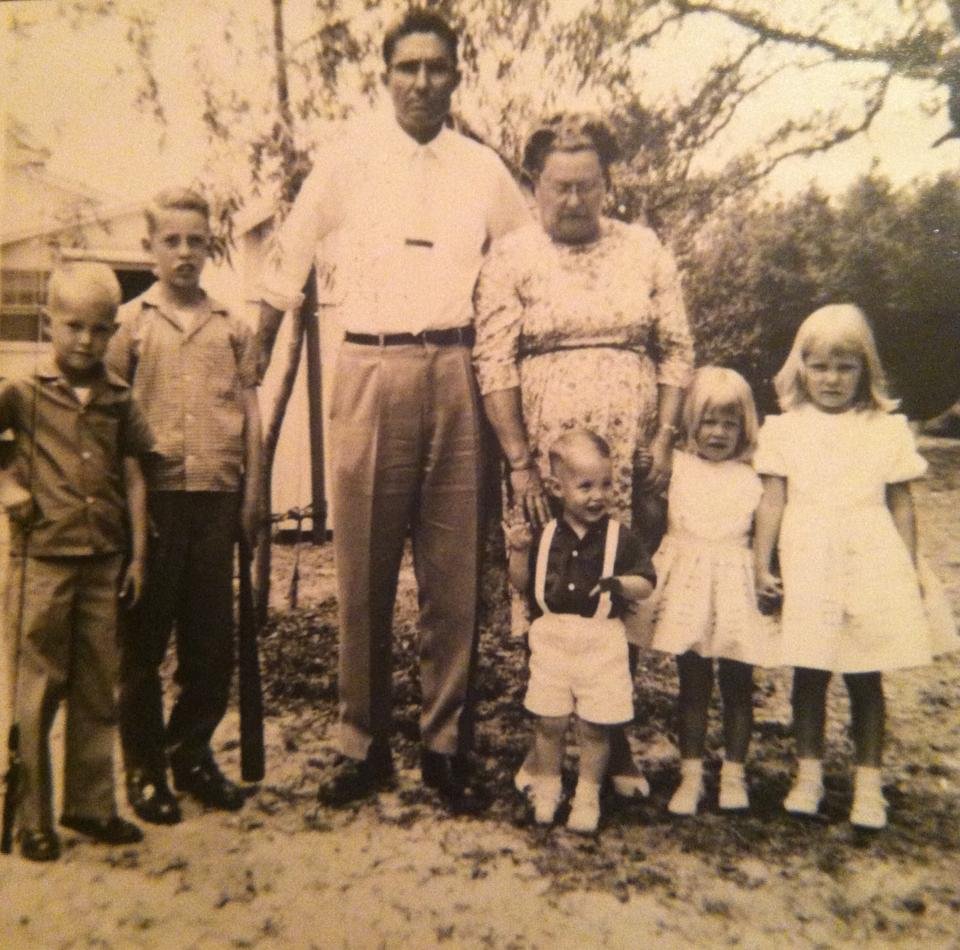

Sonny Davis, Harkers Island

Crossing the Straits on the Earl C. Davis Bridge travelers can look across the water and see Beaufort to the west and wild Browns Island to the east. The bridge leads to Harkers Island and is named for Benjamin Franklin’s first cousin Ebenezer Harker. Ebenezer moved into the area from Boston in 1730 and purchased what was then known as Craney Island.

Harkers Island is about five miles long and runs west to east. The island’s main road is called Island Road or “the front road” by locals. It traces the south-facing shoreline looking across Back Sound to Shackleford Banks and Cape Lookout, and meanders past stands of twisted live oak trees with canopies shaped by southwest winds. Drawings of the wind-shaped oaks are found on the cover of the Harkers Island United Methodist Women’s cookbook Island Born and Bred and on Joel Hancock’s history of the Harkers Island Mormon faith, Strengthened by the Storm. Hancock writes that the live oaks not only endure salty tempests better than other variety of trees, but are “made greener and fuller by the storm itself.”

Indeed, the story of Harkers Island is a compelling one of remaking a life and community in the wake of catastrophe, of mass exodus and pioneering a new land. Long-established Island families - Willis, Guthrie, Lewis, Yeomans, Rose, Hancock - are directly descended from nineteenth century Ca’e Bankers (pronounced “Cay” Bankers, short for “Cape Bankers”). Ca’e Bankers lived, hunted whales and fished off Core and Shackleford Banks until storms of 1896 and 1899 ravaged their homesteads and drove them to higher safer ground. Some went to Marshallberg, others to the Promise Land of Morehead City; but many floated what was left of their house and belongings across Back Sound to nearby Harkers Island, where they bought land for a dollar an acre.

Hancock, a third-generation descendant, wrote, “Houses were torn down board by board, loaded on skiffs, transported across the water, and then hastily rebuilt.” Other houses were “left intact, laid upon dories, and floated across.”

Ca’e Bankers flourished in their new surroundings on Harkers Island, living in kin-based neighborhoods and continuing with their trade of fishing and boat building. The population of the island quadrupled between 1899 and 1903, but the thick groves of cedars, oaks, pines, maples, and yaupon bushes remained intact with settlers staying close to the south shore in sight of their homeland and close to their fishing grounds.

Their collective identity as Ca’e Bankers was only made stronger after being compelled to leave the banks. Although natives of Shackleford have long since passed away, many Harkers Islanders had grandparents, if not parents, who were born in Diamond City, the largest community on Shackleford Banks. The story of the bankers’ exodus is told with great reverence by islanders, underscoring a deep and abiding attachment to place. “Some (islanders) feel a ‘hankering’ now and then to go back to the Banks, not as tourists go to the beach to frolic, but to stay for days – even weeks – at a time, living off nature’s abundance, relishing the isolation, the primitiveness; stirring memories remaining only in the blood,” wrote Josiah Bailey. He added that islanders return to Shackleford in order to “tend the totems over their sacred ground, and in so doing, to renew their spirit.”

An ongoing tradition, the car ride to Shell Point, seems to tap into and reaffirm the Ca’e Banker identity. To this day, Shell Point, named for the great Coree oyster shell midden once piled there, is a touchstone for locals who habitually drive to Shell Point and gaze across the water at Cape Lookout Light and Shackleford Banks. No one knows who started this tradition, but it is a daily ritual not to be broken. Newborn babies are sometimes carried to Shell Point before they’re taken to their own home. Others at life’s end make that final ride on their way to the family cemetery. The Shell Point pilgrimage is a reflection of Islanders’ deep connection to their Ca’e Banks roots.

Harkers Islanders are renowned for their tightness as a community. Sarah Page, who briefly taught first grade on Harkers Island, learned this lesson on her first day. “Not only did I have thirty-one little students sitting there patiently waiting for me, but most of the mothers came to school with their children that day,” she recalled. “I have since learned that that was sort of a custom (for) the first graders… (mothers) had their chairs lined-up around the classroom.”

Harkers Island is best known for its strong, family-based tradition of wooden boat building. Devine Guthrie started on Shackleford Banks and resumed his craft on Harkers Island, building skiffs in his backyard. His son Stacy picked up the trade, as did other island builders of the mid-twentieth century including Brady Lewis and his famed “flare bow” design and the Rose Brothers with their workboats and party boats.

Harkers Island boatbuilders have a distinctive ability to create functional works of beauty for both commercial and recreational purposes without written plans. Like the musician that plays by ear as opposed to written music, these builders work by the “rack of the eye,” creating vessels that are perfectly trim, true and seaworthy. A “Harkers Island boat is one of the best boats that’s ever been built in this country,” according to builder Calvin Rose, brother to James and Earl of Rose Brothers boat building fame. I guess it’s the type o f material, the design of the boat that we put in it, and then we put ourselves in that boat. When that boat is finished, what’s in us is in that boat and I think that’s what makes our boats one of the best boats built.”