Introduction

I was born and raised here,

and the longest I’ve been away was two weeks.

Thelma Willis, Williston

Just north of Smyrna across Wade Creek is Williston, named after early settler John Williston, the namesake of the Willis clan so prevalent Down East. Before the post office was established and the present name chosen, Williston was called Springfield.

Like Smyrna, Williston was a major boatbuilding center in the early days, turning out graceful sharpie sailboats and broad menhaden steamers. Vessels included the Regulator (1882), the Manteo (1890), and the Sickle (1910). Elmo Wade, famous for his menhaden vessels, was master builder for Willis Brothers Boatworks on the banks of Jarrett Bay. He also built models of his vessels, one of which is included in the Smithsonian Museum’s maritime collection.

Julian Guthrie took over where Elmo Wade left off, serving as master builder at Hi-Tide Boatworks at the very same site next to Elmer Willis’ clam house. The Harkers Island native built workboats, yachts, head boats, charter boats, and sharpie sail skiffs from the 1950s to the 1970s. Recognized for his craftsmanship, he was awarded the prestigious North Carolina Heritage Award in 1993. Randy Ramsey and Jim Luxton established Jarrett Bay Boatworks at the site in the mid-1980s, until outgrowing the facility.

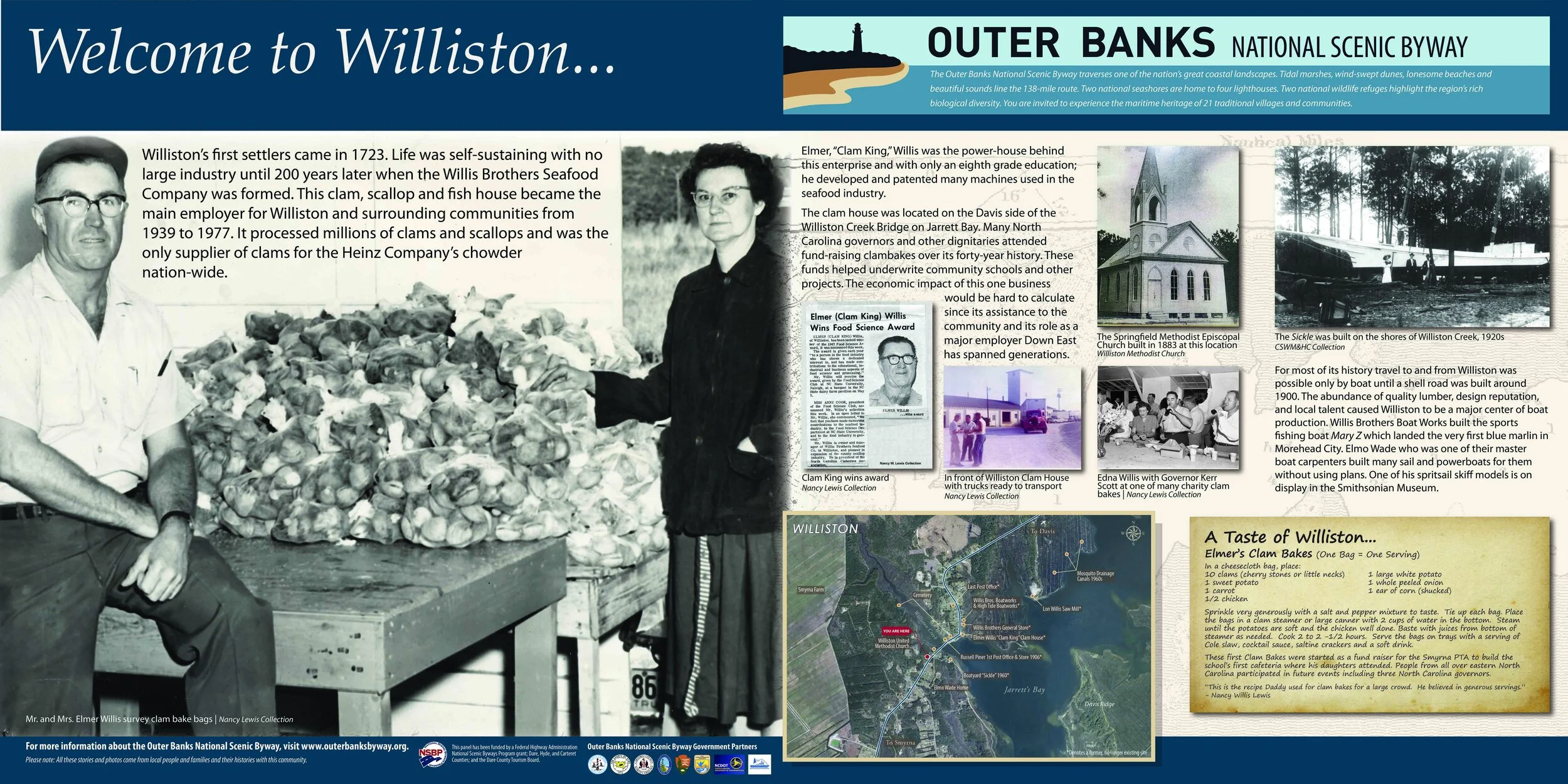

Willis Brothers Seafood, also known as the “clam house”, was owned and operated by Elmer “Clam King” Willis of Williston. “He was the sole producer of every clam that Heinz Soup Company used,” Nancy Lewis said about her father, Elmer “Clam King” Willis. Today the concrete-block clam house is falling down in disrepair on a thin piece of land between Highway 70 and Jarrett Bay. It’s hard to believe that the site was once a bustling hub of commerce from the 1930s-1970s, with tractor trailers tearing up the road with countless loads of clams and scallops. Willis bought shellfish from local fishermen. As demand grew, he also had clams and scallops trucked in for processing from out of state.

“The big clams were used for chowder, and the little ones were shipped to Cleveland, Ohio,” explained Nancy Lewis. “Did you know Cleveland, Ohio, was the clambake capital of the world?” Her father had an uncanny business sense, expanding his sales and expediting the process with inventions such as a scallop-shucking machine, for which he obtained patents.

Margaret Daniels, who grew up in Williston, recalled shucking scallops for the Clam King. “You’d go in six o’clock every morning, and you would clean and package and shuck scallops until two o’clock the next morning,” she said. The shucking machine had rollers that would “roll the gut off of them.” She worked with women who would “take their BC Powder in their Co-cola and off they go again!”

Elmer Willis held massive clambake fundraisers to help with community projects such as high school band uniforms or an elementary school lunchroom expansion. The scale of these events was captured by a News and Observer journalist in 1954, who counted 32,500 clams, 580 pounds of chicken, 1,000 carrots, eight bushels of sweet potatoes, 400 pounds of Irish potatoes, and 200 pounds of onions. “All items,” the article stated, “were distributed and tied in individual cheesecloth bags to make a total of 700 servings.” Willis was politically astute, attracting politicians of all sorts to his annual clambake, including at least three governors who made the trip all the way from Raleigh to the clam house in Williston. The “Clam King,” after all, had called.

“We were raised by a community,” reflected Margaret Daniels, one of a pack of youngsters that had roamed the shoreline of Williston. She recalled a preacher’s wife that “no one liked,” and a prank the kids pulled on her one Halloween. “She had this little bitty car,” she chuckled. “That night, we got a block and tackle and the boys climbed up the pine tree and we blocked and tackled that thing up that pine tree about twenty feet in the air.” On the school bus the next day they got a clear look at the dangling vehicle. After school they were met by parents and neighbors. “Half of Williston was waiting for us and made us get that car out of that tree.” She added, “It was harder to come down than it was to go up.”

From “Living at the Water’s Edge: A Heritage Guide to the Outer Banks Byway”

Navigation