Portsmouth

Table of Contents

To explore the various pages about Portsmouth, either scroll to the bottom of the page or click on "Navigation" to be taken to a list of subpages.Introduction

I cannot think of Portsmouth as a forsaken ghost town…

Portsmouth is an island with a soul!

Dorothy Byrun Bedwell

The village of Portsmouth, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, became part of Cape Lookout National Seashore just a few years after the residents left the island in 1971. Property owners were offered lifetime leases on their homes. The park service undertook major cleanup and restoration efforts, and continues to maintain the remarkably pristine village today.

People with connections to the windswept village of Portsmouth bristle at the term “ghost town.” The village has been abandoned since the 1970s, and the houses, church, post office, US Life-Saving Station, school, and cemeteries are still intact. But “ghost town” implies forgotten and forsaken, and Portsmouth is anything but. In 1989, the Friends of Portsmouth Island was organized to promote and encourage the preservation of village structures, sites, furnishings, and history. The Friends group, with the help of the National Park Service and many volunteers, hold a Portsmouth Island Homecoming on the island on even numbered years drawing hundreds of descendants and family connections back to the village for singing, storytelling, and revisiting family living or in family cemeteries.

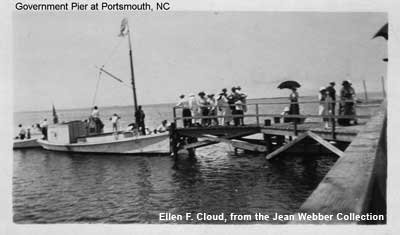

Portsmouth, like Ocracoke, began in the mid-1700s as a pilot town and “lightering” site where cargo was off-loaded onto smaller boats for transport to inland ports. The village flourished with maritime trade, and by 1810, Portsmouth was the second largest settlement on the Outer Banks. This same period saw Cape Lookout and Shackleford Banks become inhabited by seasonal fishing settlements and eventually year ‘round villages like Diamond City, Mullet Pond and Wade’s Shore.

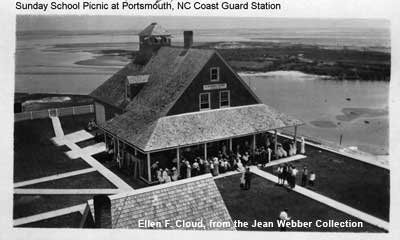

As an official commodity inspection port, Portsmouth fast became the region’s largest town, populated with merchants, inspectors, crewmen, tavern owners, and others associated with the booming business of trans-Atlantic shipping. According to Outer Banks historian David Stick, some 1,400 vessels passed through Ocracoke Inlet in 1836-37, and the growing number of sick or quarantined seamen coming to port compelled the federal government to build a marine hospital at Portsmouth in 1846. That very year, a storm opened Hatteras and Oregon Inlets, reducing the importance of Ocracoke Inlet and sending the population of Portsmouth on a downward spiral. By the post-Civil War period, almost all boat traffic had switched from Ocracoke Inlet to Hatteras Inlet. The Marine hospital closed and was converted into a weather bureau station. The thriving port town became a sleepy fishing village that was somewhat buoyed by the establishment of a Life-Saving Station in 1894.

Portsmouth of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was divided into three neighborhoods. Portsmouth Island proper was on the north end, containing houses, the Methodist Church, the school house, Life-Saving Station, grist mill, fish house, post office, and community stores. The Middle Community was less than a half mile south, and consisted of houses, the village’s only dipping vat for livestock, a couple of stores, and a Primitive Baptist Church that was destroyed by a storm in 1913. Sheep Island, about a half mile from the middle neighborhood, was separated by a creek and connected by small bridges. Sheep Island got its name from a good sized hill where sheep and cattle would congregate during storms.

Dot Salter Willis, writing with her father Ben B. Salter, in their book, Portsmouth Island: Short Stories and History, described the people there as “honest, decent, hard-working people.” The men fished, oystered, and clammed for a living and the women worked their gardens and raised their families. The homes (several still standing) were wood frame, well kept and sturdy, weathered by the frequent storms and its proximity to the ocean, sound and inlet. Portsmouth was not an easy place to live, but more than 500 people lived there at one time when the inlet lightering business was at its peak.

Oral histories recount sing-alongs on various people’s porches, simple weddings, and solemn funerals. Lizzie Pigott cut hair for villagers; when folks heard her playing the accordion on her porch, they knew she was home and open for business. Henry Pigott’s job was to pole a skiff just offshore to meet the mailboat every day, picking up letters, packages, or passengers. Frances Eubanks recalls that as a little girl, she was fascinated with Henry Pigott’s pole skiff because it was “a means of getting somewhere - the fact that he could pole it, hey he’s getting where he want s to go!”

Portsmouth Islanders, as well as men on Ocracoke and Down East, found work as hunting guides in the early twentieth century, and some attended nearby hunting clubs or lodges, catering to well-heeled businessmen in search of sport. Ten miles south of Portsmouth Village was the Pilentary Club of Core Banks. The club was owned by the Mott family of applesauce fame, who hailed from Bouckville, New York. They once had Franklin D. Roosevelt as a guest. One of the few African Americans living in Portsmouth, Joe Abbott, walked to the club every day to cook and clean for guests. He was also known to entertain them with his singing abilities. The Pilentary Club was destroyed in the 1933 storm, as were numerous others, bringing to a close the heyday of the gentlemen’s salty get-a-ways.

The Methodist Church is a most prominent and beautiful landmark in the village of Portsmouth. The original church was destroyed, along with Middle Community’s Primitive Baptist Church, in a 1913 storm. The church standing today was built around 1914. The previous church had a balcony for slaves, according to oral history accounts. Members of the Pigott family, African Americans who remained on the island into the twentieth century, sat in the back of the church. Lizzie Pigott played accordion and sang in church. Henry Pigott served as sexton in the church. “He was always there to ring that bell on time and to light the lamps,” recalled a Portsmouth Islander.

From “Living at the Water’s Edge: A Heritage Guide to the Outer Banks Byway”